In his edition of the sixteenth-century treatise attributed to Friar Roger Bacon, De Nigromancia, Michael Albion MacDonald names the fourteenth of May as the Feast of Saint Cyprian. He does so in a parenthetical explanation for why the text instructs the reader to ‘conjure in May’ as an especially pure and holy time of the year.

Certainly Saint Cyprian haunts this (pseudo-) Baconian grimoire. He is appealed to specifically in conjurations of Astaroth, Belial and other spirits, his name is inscribed in one of the several circle designs this text presents, and his Mass forms a key part of purifications and preparations for performing De Nigromancia’s various operations. As I have framed in my essay ‘‘In the Manner of Saint Cyprian’: A Cyprianic Black Magic of Early Modern English Grimoires’, in Cypriana: Old World (Rubedo Press: Seattle, 2016):

‘…Bacon – while the most frequently cited author or translator of De Nigromancia – is arguably not the actual patron of the kind of magic the book describes. Evidenced in its earliest instructions on purifications, this particular text is especially reliant on our infamous sorcerer-saint, Cyprian, as express teacher and patron of the art of necromancy. For ‘when you begin working in all operations of this Art, you must during the times of preparation for the conjurations have a Mass of Cyprian and any other Mass which is required… but the Mass must always be said in the manner of St. Cyprian, by whom it was in this Art through consequences most propitious we [became] guardians of his Secret Book…’ De Nigromancia can be thought of as the path to another, more occult – even perhaps initiatic – work, teaching the means to learn the necromancy of Cyprian itself.’

By my Hippocratic-esque vows as an historian – to do no knowing harm to the body of public knowledge – I must admit: I have thus far been unable to find any other mention of this May Feast of Cyprian beyond MacDonald’s claim. However, I see no reason not to add this to the Holy Days of the Sorcerer Saint in modern living devotional praxis. Certainly in local saint veneration around the world, a patron may have several lesser and greater Feast Days. It even seems somewhat a product of the “correspondence-list” approach to saints (“colour, number, things to use them for”) to suggest a personal patron saint – the sacred guide who becomes your trusted ‘go-to’ counsel on all matters – might only have one sacred day a year. I am content to appreciate the threads of such editorial exegesis by which the De Nigromancia’s corpus is reanimated, knotted as they are with the name of the tome’s mythic patron whispered into them.

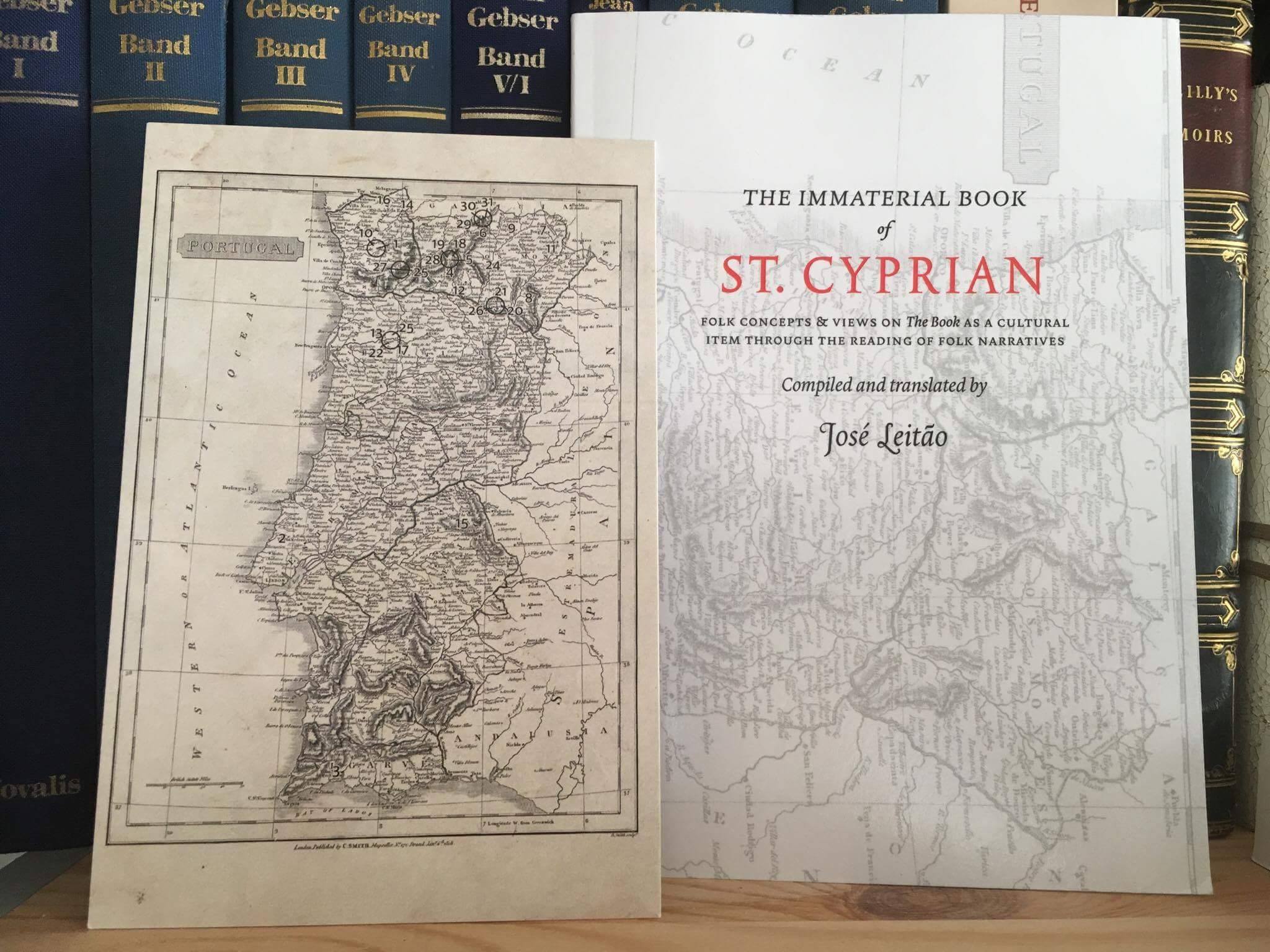

As such, it is with great pleasure I write this post to honour this May Feast with a celebration of a new Cyprianic work: José Leitão’s The Immaterial Book of Saint Cyprian. This text forms the second book in the Folk Necromancy in Transmission series which I am proud to have founded with my dear friend, Golgothic co-host and Goat, Jesse Hathaway Diaz, under the sanguine banner of Rubedo Press.

Leitão’s newest work departs from common approaches to Cyprian and his legendary Book. Rather than simply gather the various fragments of spells, rituals, and myths alleged to be or at least be in the Book of Cyprian, it instead summons the very spirit of the Book itself by charting the Iberian legends and stories about the Book and its magical potencies and readers. It is by this light we should understand the Immaterial Book’s stated mission to explicate the ‘folk concepts and views on The Book as a cultural item through the reading of folk narratives’.

The Immaterial Book presents the very faerie in the tales and the Devil in the details. It illuminates ideas of exactly who was thought to own and consult Cyprian’s Book – witches, werewolves, and shy lovestruck boys alike. It presents the folk-magical materia and techniques paired with the various material incarnations of the Book of Cyprian, such as the deployment and value of the Sino Saimão – the “Sign of Solomon” – alongside the Book’s orisons and rites. Furthermore it refines instruction on what must be perfectly read by a willing priest from The Sorcerer-Saint’s Book at the exact stroke of midnight, and hints darkly at the catastrophic effects of but a single stutter or mispronoucement. It extols the courage necessary to disenchant treasures, and deal with mighty land spirits of temptation and terror.

The Immaterial Book is an indispensible accompaniment to the variety of Books of Saint Cyprian available in the (post)modern age, from cheap pulp pamphlets to beautifully bound tomes. Certainly it is a worthy expansion of Zé’s own Book of St. Cyprian: The Sorcerer’s Treasure, published by Hadean Press, whose expert collection of primary sources and extensive erudite commentary mark it as one of the best instantiations of Cyprian’s Book. What the Immaterial Book offers is nothing short of further mythic contextualisation of the Book as a locus of unique folk magic, charting its power in the land and legend of Iberia cast outwards across the seas and into cauldrons around the world. It marks a deepening sophistication in Cyprianic devotion, research, and praxis, and I am honoured to stable it in our growing library of folk necromantic works.

I would like to leave you with a parting suggestion for exploring the Immaterial Book’s further value as a sorcerous focus. In editing and publishing such works of folk necromancy we have found interested parties often ask for clarification on whether such books actually contain magical operations (or at least instructions on these) or if they are simply about such things. As from countless magicians throughout history, magpie-eyed, the question echoes: where are spells? Given the Immaterial Book’s cartography of the enchanted treasures and legendary significances of Cyprian’s Book, I would strongly recommend those searching for these magical operations to experiment with dreamworking. Placing the modestly sized Immaterial Book under your pillow after reading it last thing at night, perhaps illuminated by a suitably dressed candle, lit from a match struck – like a deal at the crossroads – at midnight. Allow it to guide you through the crooked landscape of dream: down and across the centre-unfolded valley of the cracked spine, the marked turn, dog-eared and cats-pawed. It is held by some traditions that the historical texts called “Cyprian’s Book” are merely the material inkshod footprints of the True Book of Cyprian, which may only be read in dream. To trace the shadow of the Book is to divine its sacred heart from the silhouettes of its flickering legends.